A Legal Walkthrough

I. Introduction

Digital technologies have reshaped our world profoundly — and with ever-increasing speed. Almost every aspect of our lives has been touched by this process, in one way or the other. Different technological innovations have built and improved upon one another. We are currently witnessing the next step of this never-ending evolution in the beginning mass adoption of blockchain technology.

One area that can profit immensely from the new possibilities opening up by developing applications is Intellectual Property (IP). Seeing this potential laid the foundation for establishing InvArch, and we trust that you will be equally convinced of its disruptive potential after reading this article!

This document aims to shed some light on the legal implications of the usage of the new technological solutions InvArch can bring for IP creators and on the advantages compared to off-chain IP exploitation, focusing mainly on copyright. The goal is to build up a basic understanding of how IP used to work up until now and how it can work — better — in the future, with the functionalities InvArch provides.

We shall begin by giving an overview of what defines the InvArch protocol and its main components. After that, we look at what is generally understood under the term “IP” in a legal sense and, expressly, what copyright is. We then contemplate in detail how copyright “works” in the classical (i.e., off-chain) legal system(s) and how it can and could work in the blockchain environment (to be) created by InvArch in comparison. We will finish by touching upon other areas of IP (apart from copyright) and possible applications/use-cases of InvArch for these.

With your interest sufficiently piqued, let us start by getting an understanding of what InvArch is and get around to why its role as the first dedicated IP blockchain could become a disruptive force for this whole industry!

II. What is InvArch, and how does it function?

1.InvArch in a Nutshell

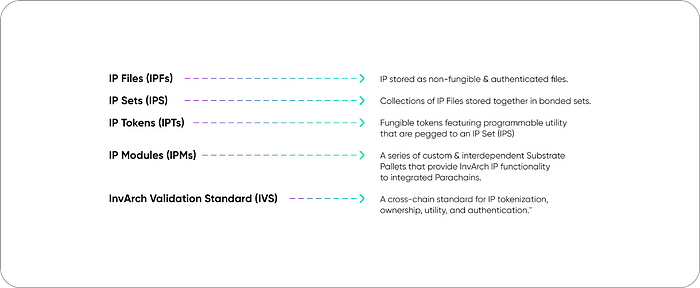

In a nutshell, Invarch is a “Cross-Chain IP Ownership and Authentication Protocol,” — but what does that mean in practical terms?

InvArch is a Substrate-based blockchain vying for the status of a parachain on the Polkadot relay chain in Q2 of 2022. Our vision is to become not a, but the standard for the decentralized development and management of IP in Web 3.0.

2. Main Functionalities

To give power to its users, InvArch will offer two main sets of interconnected functionalities — documentation and administration (primarily in the form of utilization).

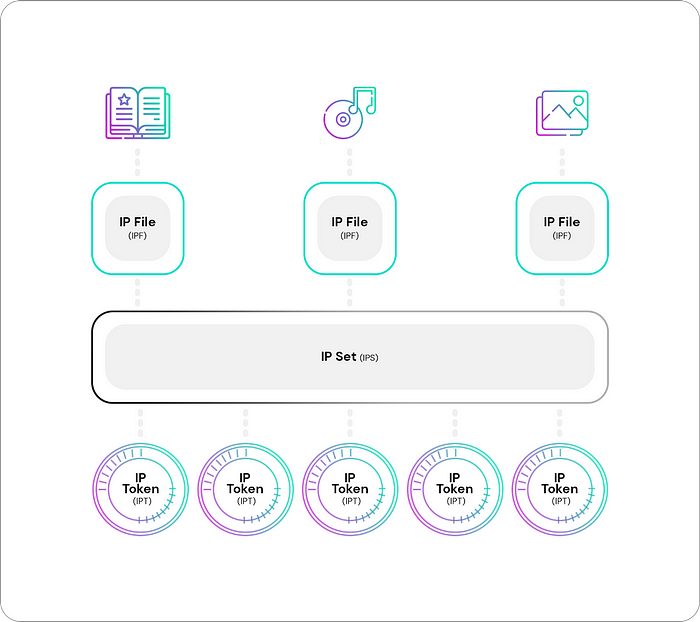

Naturally, documentation comes first: InvArch will allow users to mint files and intellectual works as Non Fungible Tokens (NFTs). These could be, among others, written creations like poems or code, sound files, 2D or 3D graphics, animations, etc. — if it can be digitized, it can be put on the blockchain! Such minted files are referred to as IP Files (IPFs) in InvArch terminology.

Collections of IPFs can be stored together in bonded sets, so-called IP Sets (IPSs). Think, for example, of several chapters that together make a book, several songs that comprise a music album, or a collection of blueprints, statistics, manuals, and instructions that enable the 3D printing, assembly, and operation of a piece of machinery.

IP thus “documented” on the blockchain is ready to be utilized! This is made possible by IP Tokens (IPTs) — these are fungible tokens featuring programmable utility that is pegged to an IPS. With IPTs, users/creators will be able to exert a whole new way of control over the fruit of their minds on the blockchain!

We will go into greater detail later on. Suffice it to say at this point that — with one click — it will be technically possible for you to, e.g., enter into a collaboration with fellow creators, “fractionalize” your tokenized “ownership” over your IP, offer licenses for royalties, and much more!

3. Other Features

Also, InvArch will not be a separate “island” of its own but connected to the Polkadot ecosystem and, eventually, the Web 3.0 via the two followings, important elements:

IP Modules (IMPs) are a series of custom and interdependent Substrate pallets that provide IP functionality to integrated parachains — in other words, they will allow other parachains in the Polkadot ecosystems to use them InvArchs functions so that IP may also be minted on these other parachains.

Furthermore, to ensure that IP minted across different chains is unique, InvArch has developed the InvArch Validation Standard (IVS). It is a cross-chain standard for IP tokenization, ownership, utility, and authentication. IVS can be viewed as an L0 standard for verifying and protecting the uniqueness of all digital assets throughout Web 3.0. All files can be minted as IPFs and have their data fingerprint indexed, cross-referenced, and protected.

Lastly, InvArch will allow for Decentralized Applications (dApps) to be developed on the blockchain (with smart contract functionality of both EVM and WASM), and the staking both of dApps and IPSs against rewards, thus further incentivizing the usage of its protocol.

Having gained an idea of what InvArch has built-in order for you to document, protect and utilize your IP, let us look into the legalities of what IP is, in fact!

III. What is IP, in general?

As a starting point, it is important to understand that “Intellectual Property” is a legal term. So, what IP is, is ultimately defined by law. Yet, as we live in a world divided, the laws differ from one jurisdiction to another. Nonetheless, in the field of IP law, there has been a continuous process of (at least partial) legal convergence in most countries for more than a century, mainly brought along by a number of international treaties on the subject.[1]Therefore, this article will neither be based on the law of one specific nation nor attempt the herculean task to cover all existing jurisdictions, but give an overview based on principles shared by most legal systems.

So, we ask again — what is IP? The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) [2] defines IP as “creations of the human mind” in their publications.[3] According to the convention establishing the WIPO, IP shall “include the rights relating to literary, artistic and scientific works, performances of performing artists, phonograms, and broadcasts, inventions in all fields of human endeavor, scientific discoveries, industrial designs, trademarks, service marks, and commercial names and designations, protection against unfair competition, and all other rights resulting from intellectual activity in the industrial, scientific, literary or artistic fields.” [4] Quite a long list — we shall have a look at some examples for IP in the following subsection in order to better understand what that entails in practical terms.

IP rights are, as a rule, intangible. What that means: the actual piece of paper upon which you write the words of a poem to your beloved or the Apple® logo on your device — they are not IP in itself, but rather only their representation in the physical realm. However, to enjoy protection, IP needs to be made manifest depending on the kind of defense aimed for. We will touch upon this later.

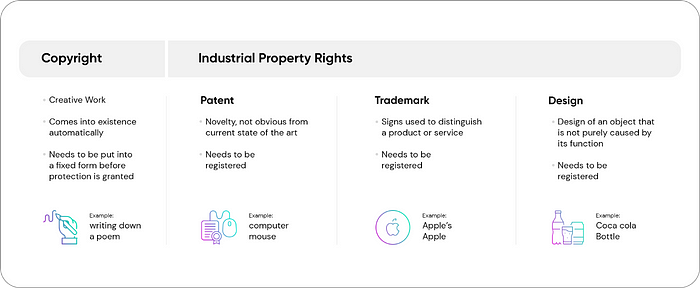

Generally, one extensive line is drawn through the field IP as a whole; two types of IP are usually distinguished: on the one hand, there is so-called industrial property which generally is considered to include, among others, patents, trademarks, and industrial designs. On the other hand, there is copyright, including artistic and literary creations.[5] There are other “species” of IP that are recognized in different jurisdictions,[6] but for this article and to keep matters concise, we shall focus on those mentioned.

IV. Practical Examples for IP

If you are not engaged in IP creation, practicing IP law, or otherwise familiar with the subject, it might still all sound rather theoretical. Therefore, to give you a practical understanding of what we are talking about before we move on, we will now take a look at real-world examples for the main types of IP that we touch upon in this article:

Copyright — we will discuss copyright in greater detail below, so it should say that this generally entails “creative works.” If you have written a short story or a line of code, painted a painting, composed a piece of music, or snapped a photo [7] — congratulations, you (probably) created a copyright-protected part of IP!

Patents — details depending on the specific national legislation, these are novel, not obvious inventions or solutions to a specific technical problem that have an industrial application; they must be granted and registered by a patent office. Examples range from things like the computer mouse to the toilet paper roll — if you are reading this article right now, you are most certainly making use of a device that was constructed with patented technical solutions!

Trademarks — these are basically signs used to distinguish a product or service, and also need to be registered with an office (for trademarks, which in many countries, are united with patent offices). Again, we remember the “Apple” logo as a sign to indicate the product originates with Apple, Inc. — maybe it adorns the device that you utilize at this moment to read these very words.

Industrial Designs — to enjoy specific protection as “industrial designs”, designs of an object must go beyond what follows purely due to the object’s function. They also require registration. An example for this kind of IP that you will probably know is the original Coca Cola bottle design!

Now that we have gained some understanding for various types of IP, let us see what separates copyright from other forms of IP!

V. Main Differences between Copyright and Industrial Property Rights

A first, very rough, distinction can be made by considering copyright as a means to protect “art”, whereas industrial property rights aim to protect “inventions”,[8] but this is a bit lacking. We do better to look at other criteria:

A major difference between the two kinds of IP rights is that copyright comes into existence automatically with the creation of the work.[9] The details may differ a bit from country to country, but as a rule of thumb — once the code is written, the painting painted, the last bit of stone chipped away from the sculpture and the work thus “fixed”, no further action is necessary.[10] The creator (in copyright context most commonly referred to as an “author”) now automatically enjoys the copyright for the period as specified by the applicable law, without the need to get any court, register or other authority involved.

The situation for industrial property rights is generally quite different. Patents, trademarks and designs do not enjoy automatic protection but need to be registered with an authority such as a patent or trademark office that scrutinizes the application and either grants it or not.[11] Therefore, they are sometimes referred to as registered rights. Also, in order to enjoy protection in more than one jurisdiction, one must file with several authorities, with corresponding costs for legal advice and filing fees (although in some cases simplified procedures for mass registering in several jurisdictions exist).[12]

The aim of industrial property as such is twofold. For example, patents help to stimulate innovation and the creation of technology, trademarks (and designs) serve to distinguish the goods or services of one enterprise from those of other enterprises.[13] We can take a closer look at copyright in the next section:

VI. What is “copyright” all about?

Copyright is concerned with the rights of the author of a creative work. As the word suggests, the historic roots of the concept — at least in English-speaking Common-Law nations — lie with the question who is entitled to produce copies of a work (a question that became — literally — more and more pressing with the advent of the printing press that made cheap copies of books possible, double pun inteded).[14]

Many other languages speak, maybe more aptly and broadly, of the “author’s right”.[15] This makes sense, as there are issues beyond copying of a work connected with it, such as its distribution (including, depending on the creation, e.g. broadcasting or performance), its economic exploitation and the earning of royalties and so called “moral rights” such as the right to be named as the author of the work, to name the work itself (giving it a title), and the right to object to any mutilation, deformation or other modification of, or other derogatory action in relation to, the work that would be prejudicial to the author’s honor or reputation.

As said above, details may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction; most countries of the world are bound by the Berne Convention[16] to apply a minimum standard of protection though (and that for a period of at least 50 years after the death of the author). Just to mention it quickly before we dive into how to capitalize on copyright — both the Convention and, accordingly, national legislation provides for exceptions to the copyright, so called “free use” cases. Examples of these are, among others, if copyrighted material is reproduced for merely educational purposes or the reporting of current events.

VII. “Classical” Copyright Exploitation (Off-Chain)

1. Basic Considerations

You plan on writing a novel or coding an app, recording a track or staging a play. And you do this with the intent of not keeping it to yourself, but to go public, to show your creation to the world, enjoy the almost inevitable fame and earn big money along the way. Maybe, to make things more complicated, you will not do it alone, but you will get others on board, co-writers, collaborators, partners? How will you reach your goals?

To start off with a spoiler: it will always come back to two main issues — if you want to protect and make good and gainful use of your creations off-chain, you will have to have good documentation and (a lot of) contract work and administration for proper utilization.

2. The Act of Creation

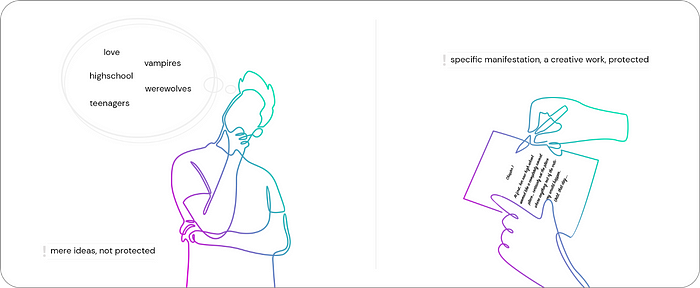

As stated above, in order for a general, abstract idea to become protected by copyright laws, it usually needs to be transferred into a fixed piece of work. Of course, this will vary depending on the work that is being created. On the one hand, the creation of a photo is effectively completed with the pressing of a button, at least as far as digital photography is concerned. On the other hand, other forms of IP require more work from their creator. I might have a vague plot (who knows, e.g. about vampires and werewolves fighting for the love of highschool girls) in my mind; yet I will need to sit down and, by hand, typewriter, computer or other way, work out the story in detail before I can call myself author. No matter if I intend to bring said story into the form of a book, stage play or movie, I have to give it some definite manifestation for copyright protection to come into play.

3. Documenting Your Authorship

In any case, it will be wise to document that you are the creator of your work. We will later discuss in greater detail how blockchain technology in general and InvArch especially can be of great use for you to easily and unalterably document and manage the IP you created. Also, chances are, if you are an artist (especially if you work digitally), you do not only create once, but you generate ongoingly, and a lot of content. In order to stay on top of your own IP output, it will make sense for you to track and organize your work.

As a creator / author / artist, you will therefore probably title (or number) your works, at least the most important ones, and affix your name (or at least your nom de plume, tag, glyph, rune or other sign of authorship that is common in your “scene”). You might keep an archive or sort of catalog of your creations, in hardcopy, digitally or maybe both. Ideally, your archive, catalog or collection should indicate a date of creation; maybe it will also contain several versions of individual works to demonstrate the creative process that lead to the final form of the IP.[17]

If we think ahead to the case of infringement, of someone using our work without our permission and, in a worst case, even claiming that they created it, if push comes to shove, we will need to engage them in a court of law and prove that we have created the IP. We will then need to produce evidence and hope that our documentation, whatever it may be, sheets of paper or digital files, will convince the court of our actual status as creator. Here we see that the fact that most jurisdictions do not have a registration process for copyright can be a two edged sword — it makes it easy to get the right in itself, but may make it difficult to successfully exercise the right!

4. Issues when Collaborating

In case you are not alone when creating your IP, but collaborating, you will be well advised to have (written!) agreements in place, from the start. While at the start of a hopeful collaboration, this may seem unnecessary due to good personal relations or because no substantial financial revenues from the IP are expected, regulating your rights (and duties) vis-a-vis each other as far as (your local) law permits should always be at the foundation of any partnership.

Depending on the legal system you and your partner(s) find yourselves in, there might be joint authorship for the whole IP (this often the case, if the contributions cannot be “separated” anymore, like when brainstorming together for the lyrics to a melody) where both have equal say. Or, partners may have differing “influence” on the fate of the IP, either because the input of one party is demonstrably larger or because the law allows for this to be set forth via agreement. Also keep in mind, in our day, often people collaborate across borders and legal systems — this may make things even more complicated.[18]

Why is this important? Well, the “fate” of the IP depends on it. Apart from the scenario where your partner might claim that your joint creation was theirs alone and tries to profit from it alone, merely being in disagreement regarding the administration of the IP can be unpleasant enough. Imagine: you and a co-author have created a software solution that turned out to be possibly disruptive. One of you is very passionate about it, the other one rather motivated by potential monetary gain. A large corporation with ample financial means approaches you both with a nigh-irrefusably generous offer to purchase your IP — with the intent of shelving it forever to prevent said disruption of its business model, or twist it in a way it was not intended for. Conflict will probably be unavoidable; having internal regulations in place may at least shorten it.

Anothering to keep in mind — depending in details on your local law, the written agreement drawn up might be actually superseded by the factual changes that occured “along the way”. It might have been agreed that four people work in equal measure to create an indie game app, but even with everybody being willing and of good faith, sometimes unforeseen things like illnesses or accidents happen that prevent people from doing their part. Should download numbers and revenue suddenly skyrocket, be prepared for discussions.

And of course, there are often enough cases of people deliberately not doing their share or even taking off with other people’s ideas. Therefore, it is important to track who does and contributes what, especially in bigger projects. If collaboration goes on for longer periods, is done on complex issues and / or with multiple / changing parties involved, this can become exceedingly difficult or downright impossible to reconstruct without the aid of information technology. Although, information technology is a broad term — we shall see later on why specifically blockchain technology and InvArch can be a game changer as a documentation tool for you and your IP collaborations!

5. Capitalizing on Your IP

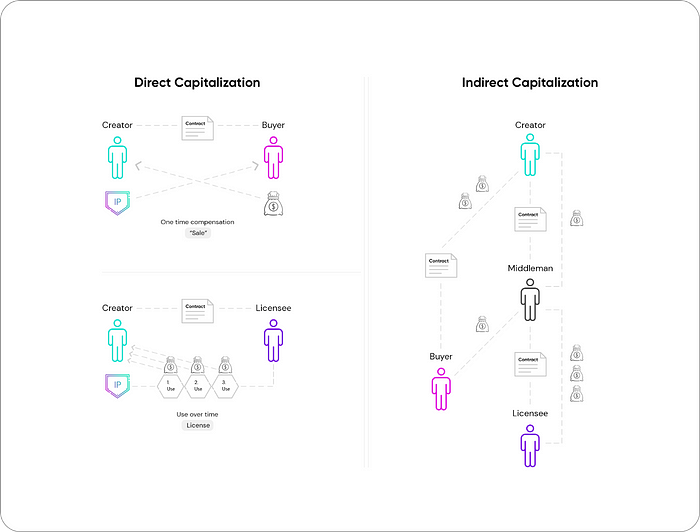

You have worked for your IP, now you want to make your IP work for you! After successfully creating that perfect piece of art, either alone, or together with others (and while circumnavigating the pitfalls that come with it, you are of one mind what to do with the fruits of your common labor), you might want two things: to get your IP out to the people (getting it published, distributed, aired, performed etc.) and getting paid. Both often go hand in hand, e.g. as a book gets published, the copies are sold for a purchase price, if a song is played on the radio, royalties are collected etc. But this is not necessarily the case: a play may be staged for free, a painting sold to a rich collector to be kept away from the public eye forever.

Depending on your IP and your preferences, monetary compensation might consist of a one time payment or in ongoing revenues. A “classical” painter or sculptor (by this, we shall refer to someone who creates their art as was done before the advent of computers) who choses to sell individual works will usually only be able to collect one time payments on each of them. A photographer on the other hand, whose stock photos get used again and again by different clients via license agreements can expect to collect regular income from them.[19]

But how to get people to pay you? You can attempt to do it directly, yourself. To print your own book and sell them yourself, or carry your self recorded tracks around — which is exactly what some nowadays very successful people have started out with. Some works of art are more apt for self sale than others, especially if you do not have to rely on a high number of sales. If you are a painter fortunate enough to be able to live off the sale of one of your oeuvres for a few months, you might handle your transactions yourself without a sweat. If you are a music artist in a time where a track is sold for a few cents, you will probably find it hard to generate the necessary volume on your own.

The solution in the latter case often is to turn to middlemen. Publishers, agents, corporations that will help you to exploit your IP for a share of the profit — often enough, a lion’s share. Again, there are different models, the main difference usually being between a one time payment and ongoing participation in revenues. In some industries such as music, the national markets are dominated by copyright collectives that hold de jure or de facto monopolies.[20] As you can imagine, their negotiating power both vis-a-vis IP-creators and the “consumers” of the created content is crushing, deals usually are “take it or leave it”. It was an evil deemed necessary though, as otherwise it would have been near impossible for e.g. music creators to prevent unauthorized use of their creations by bars, restaurants, event organizers etc. But times they are a-changing; and it might be time to cut out the middleman and secure the lion’s share for yourself… we will get to that shortly!

6. A Quick Recap

As we have seen, if you intend to create not merely for your own pleasure, but with the aim of having your IP published and earning money with it, this means administrative work apart from the creative work, consisting of documentation and contractual / legal activities.

You might face dangers, from within and without, by people who seek to take any profitable IP from you for their own gain, difficulties in aligning with co-creators regarding the fate of your IP, and disagreements on who contributed what and when to a project — all this possibly before you earned a single coin.

Even if all this works out, turning a profit still requires further hassle, either by selling or licensing your IP to buyers or licensees yourself, or by finding and brokering a deal with an agency who does these things for you — which will cost you though.

VIII. Copyright Management “by InvArch”

One thing to keep in mind about all that follows: different jurisdictions are on different levels when it comes to their acceptance and progressiveness with regards to blockchain technology, tokenization and smart contract utilization, so not every functionality described below will be compatible with every local legal system. You are on the bleeding edge here, where new ways of doing business enabled by novel technologies meet legal traditions partially dating back millenia. Not every jurisdiction will venture forth as boldly as, say, the microstate of Liechtenstein that met the 21st century head first by introducing a law on blockchain technology already in 2019; more formalistic countries might not award (full) legal protection to (only) blockchain / token based agreements (yet).

- Introductory Remarks

After spending some time on how tedious these things can be in the system(s) we have now, let us finally proceed to where things get really interesting — to the way InvArch can smooth out those bumps on the road to your successful IP management and utilization!

As we have seen above, you will profit greatly from a technical solution that makes both documenting your copyright creation and administering your IP as easy as clicking a button! InvArch and the dApps to be developed on the basis of its protocol will do just that for you!

2. “Registering” Your Copyright on the Blockchain

Copyright comes into existence with the act of creation, by fixing your idea into a specific form. You may choose to work in the presence of witnesses or even a notary (yes, this is irony), but often enough, no one will be present.

By minting your copyrighted creation as a non-fungible IP File (IPF), it is stored in an immutable way on the blockchain, with a timestamp. Whatever it is, a text file containing a short story, a picture, a 3d graphic, a sound file or any other file, you will have inalienable proof that at this specific point in time said file was in your possession and minted by you. We have mentioned before that the great advantage of copyright — that there is no register — can be one of its greatest disadvantages. With InvArch, the disadvantage is eliminated — InvArch will be your public register, and you can be your own registrar with just a few clicks!

Works are automatically dated, and you can sort them into “libraries” by combining IPFs into IP Sets (IPSs). It will also be possible to organize several IP sets into bigger IP sets, creating a nested structure- You can also keep track of different versions, if you choose so! With applications to be developed on the basis of the InvArch blockchain dedicated, you can expect the evolution of a system of fully fledged decentralized IP management software.

Ultimately, this system provides you both with a way to order and structure your IP database, and with irrefutable proof that a certain IP was in your possession at a certain point in time, indicating that you are the author. This can be used as a mighty tool to defend yourself in case someone contests your right to use your own IP, or to prevent others from unlawfully using your IP without your permission, in case you ever need to enter into legal action!

Moreover, the InvArch environment will automatically check newly minted IP against other IP already in the database for plagiarism. This will help so that no one else falsely tokenizes IP that has already been tokenized by you.

We will now look at interactions with other parties, but first we shall touch upon the topic of smart contracts which form an important element of interactions with others on the blockchain.

3. Smart Contract Functionality

We have talked before that InvArch helps you achieve your goals partially via built in smart contract functionality, but how does a smart contract (for IP) work? Contrary to their name, smart contracts are not really smart (in the sense that they are not employing strong AI); whether or not they are contracts is debated.

A famous definition that dates from the 1990s (and thus long before the advent of the blockchain), which still enjoys widespread acceptance today defines smart contracts as “computerized transaction protocol that executes the terms of a contract“;[21] the contract that the program executes must, somewhere and somehow, be concluded according to this definition. There are other definitions and opinions, some authors hold that smart contracts do not need any law at all (“code is law”)[22], others assume that they can be a means for contract conclusion.[23]

These discussions aside, in the field of copyright, in many legal systems, as intangible assets, contracts regarding them require little to no formalities in most legal systems — which makes them perfect for smart contract application. If there is no requirement to set down e.g. the license agreement in a specific written form (or even to go to the notary like with certain real estate or company law related transactions), then the contract itself can theoretically be concluded via a click and executed by the smart contract with tokenized IP assets.

Contract conclusion and fulfillment can happen immediately, in real time, and without intermediaries like banks and lawyers, and without manipulations of the transactions. For example, a smart contract can work along the lines of: “IF amount X of bitcoin is received THEN transfer ownership tokens of IP to buyer’s address”. However, there are a lot, even more exciting options possible, e.g. “(everytime!) IF IP is accessed, deposit amount X of bitcoin into (creator’s) wallet” (which would be an access based license fee). We will get to a number of examples towards the end of this article!

4. Multiple Creators

As we have discussed, in practice it is often the case that the creation of an IP will not be the work of one person, but of several individuals. By allowing several contributors to combine their IPFs into one IPS, that collaboration can be documented on the blockchain. It will work for any kind of IP that can be stored as a digital file, so examples that come readily to mind are people contributing individual chapters for a book, code modules for a software application, individual pictures or tracks for a photo or music album etc. However, the IP does not have to be of the same sort. A team works, e.g., on the creation of a computer or mobile game — in that case there will be coding, 2D or 3D modelling, promotional material, maybe lore texts, sound files etc., which all can be part of one IPS.[24]

So here we dive right into the crossroads of documentation and administration! By using the structure provided by InvArch, each and every contribution is documented and 100% trackable, even years later and even in the most complex projects. But InvArch does not only serve to record who did what when, but can also be used to set forth the rules to decide what follows from these specific contributions to the common cause. So, how does that work?

In order to regulate your relationships inter partes, you will be able to create IP Token (IPTs) that are pegged to the IPSs (or, if you combine several IPSs into one, to the resulting IPS-megaset). With these tokens, you can easily and via smart contract functionality define the relationship between the different creators involved, such as “ownership” over the IP — in this sense are akin to ownership “certificates”. However, the functionalities are not limited to this. The IPTs’ potential is far greater, they are true chameleons. They can be programmed to grant rights to receive royalties or act as access rights to the linked IPFs (and thus basically as “keys to the vault”). And, just by the way, if you are ambitious and plan to program your own dApp on InvArch, you can go ahead and use IPTs directly as currency on your dApp!

Most importantly, they will be a swift and effortless way to regulate the governance of your project, meaning that they can be utilized to grant voting rights to holders. Such rights can be corresponding to ownership percentage, but that is not necessarily the case. You will be saving a lot of time by adjusting the relationships with co-creators in this way instead of setting up classical written agreements and holding formal meetings (and taking minutes). Often enough though, people do not even do this at all though and precisely for this reason: because it takes time and is complicated. Also, due to the way human interactions and minds tend to work, there is a certain mental barrier for many people to have legal papers signed at the start of a collaboration when things are in a flow and good energy is abundant. InvArch can help you make things less awkward by transforming this procedure into a form that most are more comfortable or familiar with — setting up your rights and duties will be the same as setting up an account with a software or a config in a game.

IP with multiple creators can thus be managed on InvArch like a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) — roughly analogous to a corporation in conventional legal systems.[25] Creators have rights to the IP itself, as can be compared to a share in a company, and rights regarding the fate of the IP, analogous to voting rights in the company. And, just as a company — in a best case scenario — makes money and shareholders are entitled to a share of the profits — tokens give claim to a share of revenue from IP exploitation.

So far we have spoken about internal matters, let us now set our eyes on interactions with the outside world:

5. Transferring Rights and Obligations

As we have discussed, if you have created a copyrighted IP not merely for the pleasure of keeping it within your own four walls (physical or digital), you will want to have it published and used by other people against compensation. Again, as discussed, compensation can usually be a one-time payment, or an ongoing stream of royalties.

Some legal systems allow for the actual ownership in the copyright to be passed on (either against compensation or for free), others only allow for the rights of usage to be transferred (while the right in itself, perhaps “quite naked” remains with the author) — the practical effect is mostly the same though. By tokenizing the ownership and/or rights to usage of the IP, those rights can then be transferred with the tokens via smart contract to other addresses on the blockchain — with a click.[26] The conditions for the transferral? You set them! A one time payment in crypto currency? Done. A fiat payment? Possible in the future too, with oracle integration. License fees / royalties, either as a fixed sum for a period of time, or based on per use? You name it. “Full” rights, or shall the new address be limited, e.g. not be allowed to sublicense the IP? All possible. The token representing the rights and obligations is transferred, and thus the rights and obligations with them, without the need of a classical (written / hardcopy) agreement.

As opposed to off-chain rights transferral and licensing, this procedure has a number of advantages. For one, the “track”, from the original creation of the IP and the chain of licenses and sublicenses is continuous and without interruption on the blockchain. The last rightful user on the blockchain will always be able to demonstrate that their right ultimately stems from the original creator; the creator can, vice versa, always ascertain their authorship and, e.g. in case of misuse, might retract the IP. We have read it before, tokens can act as “keys” to IP vaults; the blockchain can also serve as a way for a sublicensee to proof that they have passed on a IP and are not using it themselves at the same time (thus avoiding the “double spending” problem e.g. in connection with software licenses).[27]

6. Getting Paid

We have seen how easy it is to sell our license you IP on InvArch, the same holds true for collecting the rewards to the transferred rights. As we have discussed above, smart contracts in connection with tokenization make it effortless to define the conditions under which payments are due. Lots of different models are theoretically possible, like a classical “sale” of an IP, time based usage or access models (e.g. the right to use / access for a day, month, year etc.), usage based remuneration etc.

You are able to forego the classical middlemen of off-chain exploitation and thus increase your profits. Moreover, on InvArch’s blockchain, you can collect on usages that otherwise would be too minuscule or hard to track. Off-chain, you would not (or simply could not) bother to request payment, e.g. because the costs in terms of financial means or time for identifying the payment obligation, collecting the payment, or enforcing it are higher than the payment itself. With InvArch’s technological solutions and smart contracts, no contract “maintenance” is necessary. The code “knows” if the predefined conditions are fulfilled, without your needing to check, and automated payments (e.g. micro-payments in a crypto currency of your choosing) can be collected.

If you still want or need to share, received financial compensation can also automatically be distributed between different actors. Co-creators can receive equal or weighted shares (in relation to their “ownership” of the IP) of any monies received — a “horizontal” split or fractionalization. But also a “vertical” distribution can be imagined, where license fees paid by the last sub-licensee are handed “up” in the chain and split between the original creator(s) and those in between them and the paying customer.

Depending on the arrangement, additional strengthening of the creators’ position can be thought of, like automatic sanctions in case of contract violations — that could start with automated reprimands, including temporary or permanent blocking of access to the IP, penalty payments from deposits etc.

As payments can be effected immediately and without the need for intermediaries, creators can exercise a whole new level of control over their IP and their exploitation for commercial gain! Since we have pondered the possibilities on a rather abstract level so far, we will look now into practical examples:

7. Practical Examples for a New Copyright Ecosystem with InvArch

As demonstrated, InvArch is packed full with functions as it is, but we furthermore expect a whole ecosystem of (decentralized) applications to develop on its basis.

You can envision blockchain/InvArch-based (decentralized) platforms for the consumption of IP — music or video streaming, like spotify or netflix, but with the IP tokenized in the background and royalties paid-per-use. Or gateways / libraries with access to research or technical data based on the same principle. Any consumable IP behind a paywall these days is apt to be tokenized and decentralized this way.

Another use case would be (decentralized) platforms where IP can be licensed for further usage (“incentivized open-source collaboration”). Imagine e.g. shutterstock, but based on the blockchain — envision the images created while using copyrighted material; from any profits received by the creator of the second image, a certain share can be deducted and transferred automatically to the original creator of the first image. The same could be possible e.g. for music — the creator of a beat could make it accessible on the blockchain, any other artist that incorporates it in their tracks has to pass on a certain share of eventual profits generated by the music. The basic principle is to start to build toolboxes or libraries with modular IP that can be combined, incorporated, built upon etc. by other creators. This model can be put into effect with any IP that can build upon each other — one could title it “stacked” IP. It could work e.g. for sound effects for movies or video games, 3D models for renderings or games, code blocks for software etc. etc.

In general, InvArch can act as a platform for (decentralized) applications that allow project collaboration, decentralized communities of developers will be able to work on projects in a flexible and at the same time safe manner as never before. It will be possible to manage IP relations with regard to all different sorts of IP, such as IP existing prior to the cooperation (background IP) and developed during the cooperation (foreground IP), but also parallel (sideground IP) and thereafter (postground IP).

InvArch can serves as the basis to build up a (decentralized) Enterprise IP Management System — no matter how different the two companies are, and regardless of the IP management application of their preference, as long as these applications are built using the InvArch protocol, the digital IP assets existing among them will be interoperable throughout those applications. This streamlines the process of multi-enterprise IP management and collaboration.

An iDEX (IPOwnership DEX): Entire marketplaces and decentralized exchanges (DEX) could be created in order to provide lucrative mechanisms for IP fundraising. Whether a simple DEX for trading IP Tokens of certain projects, or even marketplaces for fractional ownership, the financial barrier to opportunity is lowered for interested parties, and ways to fuel innovation are increased for developers and founders.

There might be lots of other ways to further play on the decentralization effect, such as decentralized and incentivized education: educational material, such as lectures can be minted into IP Files and combined as IP Sets in order to form entire courses and even entire education systems. IP Tokens could be programmed to be minted upon contribution to a course or system, as well as freely distributed to its participants. This mechanism could allow for community-governed education systems. As far as we know, there is no blockchain university yet — and perhaps Oxford, Harvard or Yale, for all their academic splendor, are not the right place for such a university, and the best place is the blockchain itself! And, who knows, since you are reading this article, you yourself might want to contribute?

We have seen how InvArch is an extremely powerful tool with an abundance of possible use cases — we hope that we have got your mind going full speed now, thinking of other applications! But we are not yet done and will touch upon a few IP use cases that go beyond copyright:

IX. Other uses of InvArch regarding Intellectual Property

An important industrial property right[28] are patents. We learned that they require as a prerequisite for being granted that they are “novel”. Most legal systems have no territorial limitations in this regard. This means, they must be new to the world as a whole, not only to the country for which patent protection is sought. Thus, if an invention (including the steps that lead to them from the former state of the art) is put on the blockchain, it is an excellent proof for one’s own position as inventor at at specific point in time for one’s own patent application and a perfect tool to challenge someone else’s patent application or granted patent that happened after the minting (even if one does not yet have a patent or, for whatever reason, cannot expect to receive one). Due to the high technical reliability of this proof, it is a strong argument why patent offices should accept it. This has not only a positive effect for the original invention / patent in question, but also for any patents that follow after it if they build on the original patent. Putting the information on the blockchain can be a way to “get it out there”, even before an actual patent application. Analogously, one could use it to document other priority relevant information, e.g. in connection with trademarks.

We hope to see the adoption of InvArch’s technology also by registers for patents, trademarks etc. At this point, before this happens, it is important to know that InvArch will “crawl” publicly available register data — this is part of the built in anti-plagiarism automatism of InvArch that will prevent that will aid to prevent the misappropriation of already registered IP.

Speaking of having InvArch becoming the solution of choice for classical industrial property register — this would bring benefits for everyone. Apart from the fact that this would lead to real interoperability between all the register offices that switch to InvArch, it would turn “old school” IP into smart IP. Users could register and administer (i.e. prolong, transer, license etc.) patents, trademarks and designs transparently and and with unalterable record thereof via smart contracts, including payments to reduce transaction costs and time. That would also help with the issue that IP in classical registers is often not adequately maintained — not every transfer, update, etc. is entered into the register, licenses generally are given by agreement and cannot be inferred from the register. With InvArch, this can be different! All that has been said above with regard to the benefits of smart contracting and administration of IP could then also be made applicable to industrial property rights.

Some legal systems consider the protection against unfair business practices to be part of IP law, among them the protection against certain acts of blatant (“slavish”) imitation — this is closely related to copyright. As an example — a designer of jewelry creates a set of matchings rings, bracelets, necklaces, earrings etc. Perhaps they can be deemed to be protected by copyright according to the local law, perhaps not. Protection as industrial design could come to mind too, but for the example, we assume that this would have been too troublesome and costly for our designer. Too bad, since a competitor whose lack of creativity matches their low moral standard copies the aforementioned set of jewelry exactly. Luckily for our designer, they have had the wits to mint sketches, 3D renderings and photos of the finished products as an IPS on InvArch, documenting their creative process and priority in time. Therefore, the hapless competitor stood no chance when faced with a legal action to cease and desist, report all profits made with the counterfeit jewelry and to hand over said profits to our original creator.

InvArch is generally about transparency — however, you can use it also to be more than secretive. You want to document that you are in the possession of a specific file, but you do not even want to entrust it to the blockchain? Easy. Just mint the hash of the original file — should you ever then come into the situation where you need to prove your ownership you will be able to do so, as was demonstrated in a famous court case (from China even, mind you!).[29]

We think there are as many applications for InvArch as there are creative minds, and with the further development of technology, these will only increase!

X. Closing Remarks

This article should have given you a general idea of what InvArch is about in a technical sense, a rough understanding how IP (and copyright especially) works in the majority of legal systems and — most importantly — how InvArch can revolutionize this!

As we have seen, despite differences in local jurisdictions, two tasks will constantly plague you as an IP creator who wants to publish and flourish — the documentation of your IP, and its administration. This can be simpler in some cases, e.g. if you are a classical painter in your artelier, selling half a dozen paintings a year to collectors and traders. Or it can be most taxing, for example as one of many contributors in the development of a rather unorganized indie computer game, or electronic music creator, trying to carve out a living from a few cents per download of your tracks.

InvArch has the ambition to be the solution to many of the hardships connected with classical off-chain IP management; we have developed the technology to document, transfer, license, sublicense, vote on, give access to and handle IP in many other ways in an effortless and revolutionary way. We aim to become nothing less than the backbone, the foundation of IP management in the Web 3.0.

From a legal point of view, there are many arguments for the usage of InvArch’s technology, especially as the streamlined, “easy-as-clicking” documentation it provides that will support our users also in the conventional legal systems. The law is a behemoth, it moves slowly, yet it is our deep belief that things are now in motion that cannot be undone. The factual developments that are currently taking place will affect legal evolution, as lawmakers cannot afford to ignore them, and, just as the Web 1.0 and the Web 2.0 effectively could not be stopped, neither will the processes that move us towards the Web 3.0. At InvArch, we look forward to not merely being objects of this change but doing our share to influence the events that will lead to a new fusion of technology and law!

Authored by Rainald Koitz, IP & Copyright Advisor for the InvArch network.

Endnotes:

- For example, the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, adopted in 1883, was one of the first major steps taken to help creators ensure that their intellectual works were protected in other countries. After a series of revisions, it is still in force today. One of the latest additions to these treaties is the Beijing Treaty on Audiovisual Performances, which was adopted on June 24, 2012, and entered into force on April 28, 2020.

- The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) is an agency of the United Nations, established in 1967. It serves a number of functions. Among those, it administers the aforementioned international IP treaties, provides a forum for IP policies and laws, IP filing, dispute resolution etc.

- WIPO, Understanding Industrial Property², https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_895_2016.pdf, retrieved on 12.12.2021.

- Convention Establishing the World Intellectual Property Organization (Signed at Stockholm on July 14, 1967 and as amended on September 28, 1979).

- Cf. e.g. Fact Sheets on the European Union: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/ftu/pdf/en/FTU_2.1.12.pdf, retrieved on 12.12.2021.

- E.g. Utility Models, Designations of Origin, Trade Secrets, Plant Varieties, Trade Dresses, Integrated Circuits, etc.

- Depending on your local jurisdiction, other criteria need to be fulfilled, e.g. your work needs to reach a minimum level of originality, and — naturally — cannot be just a copy of an actual original and thus copyright protected work.

- WIPO, Understanding Copyright and Related Rights, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_909_2016.pdf, retrieved on 12.12.2021.

- A notable exception in an important jurisdiction: while signatory to the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, the United States of America still requires the registration of a copyright in domestic cases in order to file an infringement suit (also, a registration grants advantages when claiming statutory damages, attorneys’ fees and costs).

- Note that the mere idea in the mind is not sufficient, this will be important later on.

- Again, the authorities need to be presented with a representation or description of the IP, e.g. a drawing of a logo that one seeks trademark protection for, either as a hardcopy on paper, or, more likely these days, as a digital file via e-filing.

- E.g. filing a patent in several countries in the procedure of the Patent Cooperation Treaty, or seeking trademark protection as a European Union Trade Mark (EUTM) that grants protection in all EU member states.

- Cf. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/intel1_e.htm, retrieved on 12.12.2021.

- The British Copyright Act of 1710 is considered to be the decisive law that laid the foundations for copyright as a publicly granted right in common law.

- Among others, for example many Slavic languages like Russian, and Romance languages like French or Portuguese.

- Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works of 9. September 1886.

- A famous example, though “in reverse”, is Pablo Picasso’s “Le Taureau”, a series of eleven lithographs, where the artist deconstructs a bull, from a more realistic to an increasingly abstract form, whereby the creative process is made visible. The art itself can be seen here: http://mourlot.free.fr/english/fmtaureau.html, retrieved on 12.12.2021.

- The issues in connection with the enforcement of rights in a globalized world with vastly differing legal standards are legion and are not the focus of this article. Problems range from calamities such as uncertainties as to the appropriate legal venue and applicable law, infringers operating out of countries with defunct or at least severely inefficient judicial systems, to the simple fact that cross border legal action can be so complicated and cost intensive as to be simply not an option for small individual creators. However, we will touch upon how — with the usage of so called “smart contracts” — some rights and duties can be automatized, thus eliminating the need for “classical” court systems partially.

- Basic economic considerations demand either to produce / sell frequently, or, alternatively, for a greater price.

- For a little dive into the world of collection collective, check out CISAC — the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers’ Global Collections Report (2021) here https://www.gema.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Aktuelles/CISAC_Global_Collection_Report_2021_EN.pdf, retrieved 12.12.2021.

- Smart Contracts, Nick Szabo (1994), https://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/rob/Courses/InformationInSpeech/CDROM/Literature/LOTwinterschool2006/szabo.best.vwh.net/smart.contracts.html, retrieved on 12.12.2021

- A line of thought made popular by Lawrence Lessing in his book Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace dating from 1999. If one reads the original text though where the phrase is coined, it is clear that the main argument is that code shapes the very reality of cyberspace and it is thus of high importance what choices are made as to how this reality is programmed. It does not stipulate the supremacy of code over “conventional” law. An updated version of Lessing’s book is online for free here: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fd/Code_v2.pdf retrieved on 12.12.2021.

- An easily understandable analogy for this theory can be a vending machine. Just like with a smart contract on a blockchain, you may not know who put it up, just as the person who put it up might not know who will stop to buy a snack. There is merely a slot for your coins and some candy bars on display through the looking glass. No written contract is drawn up, just this: coin goes in, snack comes out, transaction concluded. Now, the vending machine is not the contract itself, but it is the executing means by which it is concluded and carried out.

- This article focuses on copyright, but of course, InvArch is just as useful when it comes to documenting technical data, e.g. blueprints or other material needed for the construction of machinery.

- The exact nature of DAOs remains highly debated, although as per July 2021, the US State of Wyoming recognized DAOs as legal entities in the classical sense — if they abide by certain rules (which some criticized as taking away the truly decentralized character of a DAO). Cf. e.g. https://sos.wyo.gov/Business/Docs/DAOs_FAQs.pdf retrieved on 12.12.2021.

- NB: Details how jurisdictions view tokenization and transferral of rights and obligations via tokens / smart contracts cannot be answered in a generalizing way but will depend on the individual country.

- E.g., for the European Union, the European Court of Justice ruled in 2012 (C-128/11) that in the field of software licenses, the granting of a perpetual license for a one time fee is de facto equal to a sale and therefore the software developer cannot hinder the licensee to pass on the software to a third party. Prerequisite however, is that the licensee can demonstrate that their original copy has been made unusable. Blockchain technology can make sure that only one licensee at a time has access to the licensed IP.

- For the difference between copyright and industrial property rights see above.

- https://go.dennemeyer.com/hubfs/blog/pdf/Blockchain%2020180726/20180726_BlogPost_Chinese%20Court%20is%20first%20to%20accept%20Blockchain_Judgment_EN_Translation.pdf?_gl=1*1d69fml*_ga*MTg4OTU1MDU3MS4xNjM5NTY2MzA1